1 Introduction

The Commission started by looking at how Parliament could use digital technology to work more effectively and in a way that people expect in the modern world. We also considered how digital could enhance the voting system, as this is a fundamental part of the UK’s system of representative democracy. We asked people to tell us their views online or in person and we heard from a wide a range of people. They included not just experts, MPs and interest groups, but members of the public—people of different ages and backgrounds and people with varying levels of interest in politics and the work of Parliament.

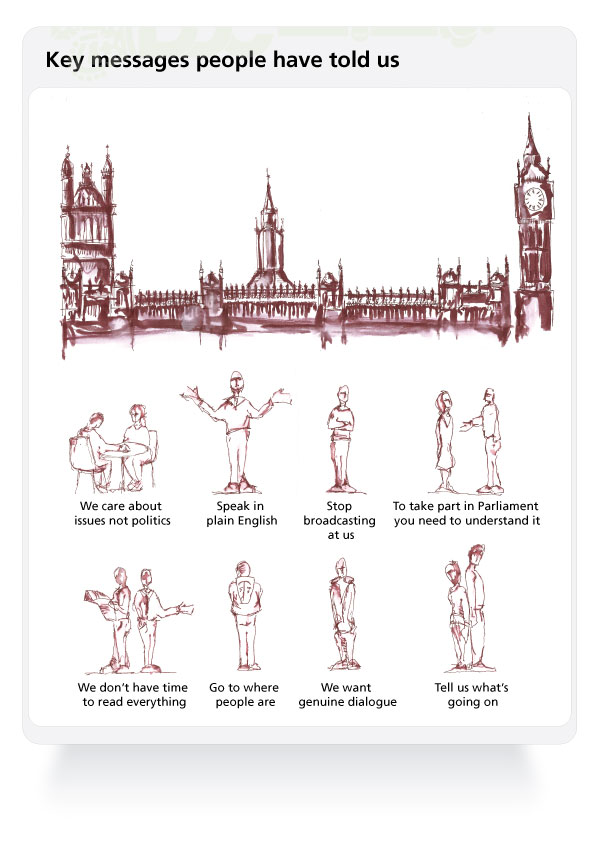

This image shows the key things people have said to us. These are: Go to where people are; Speak in plain English; To take part in Parliament you need to understand it; We care about issues not politics; We don’t have time to read everything; Tell us what’s going on; Stop broadcasting at us; and, we want genuine dialogue.

This image shows the key things people have said to us. These are: Go to where people are; Speak in plain English; To take part in Parliament you need to understand it; We care about issues not politics; We don’t have time to read everything; Tell us what’s going on; Stop broadcasting at us; and, we want genuine dialogue.

One message that resonated very clearly was that digital is only part of the answer. It can help to make democratic processes easier for people to understand and take part in, but other barriers must also be addressed for digital to have a truly transformative effect. As the Democratic Society put it:

“[T]echnology in itself is not a panacea and it will not effectively correct poor existing practices…we need to look beyond new digital tools to existing processes that do and do not work, and then critically explore how technology can help us to make democracy work better.”[1]

1.1 Barriers to engaging with Parliament

As people told us about their experiences of voting, contacting their MP or finding out about Parliament—or why they do not do those things—some of the barriers to getting involved became clear. These included:

- lack of understanding about politics and Parliament

- jargon and unclear language

- difficulty finding information about Parliament and its activities

- feeling that Parliament is not relevant

- feeling that participating will be pointless and that politicians do not listen

- lack of opportunities to be involved with Parliament

It is imperative that these barriers are addressed if every UK citizen is to have equal access to democracy in the UK. We already know that some people are more likely than others to take part in activities such as voting, signing an e-petition, or trying to influence political decision-making.[2] For example, women, people from lower socio-economic groups, young people and the less educated are less likely to be politically engaged.[3] This means that some groups are having more of a say than others. So, taking action to address the barriers we have outlined will not only make Parliament more accessible, but might also help to increase the diversity of people who are politically active.

1.2 Overcoming barriers

Not everyone wants to vote or to take part in the political decision-making process, but people should not be prevented from taking part because they do not understand how to, or because they do not feel confident enough about their political knowledge. In our report we focus on how the barriers we have outlined could be overcome. The main areas we look at are:

- improving public understanding about politics and Parliament

- reducing jargon and making language easier to understand

- making it easier to find out what's going on in Parliament

- relating Parliament’s work to people’s lives

- reaching out to under-represented groups

- widening opportunities for genuine participation

- tackling digital exclusion

- ensuring the public have a good experience of engaging with Parliament

- elections and voting

We focus mainly on what Parliament could do, using digital technology, to achieve these aims. Where appropriate, we highlight the actions that other bodies could take to increase access to democracy. We also discuss how to ensure that people who are less able to take advantage of digital are not left behind as democracy becomes more digital. Finally, we outline what a fully digital Parliament might look like, and highlight some of the tools and skills that will be needed to bring it into being.

Parliament is made up of two independent bodies, the House of Commons and the House of Lords. Although our recommendations are addressed mainly to the House of Commons, we hope that they will also be of interest to the Lords, and we know that many members of the House of Lords follow digital developments closely. We have often referred to Parliament rather than the Commons because digital services will better meet the needs of the public, as well as being more efficient, if information about both Houses of Parliament is fully integrated and available in the same place.

[1]Digi058 [Democratic Society]

[2]Hansard Society, Anti-Politics: Characterising and Accounting for Political Disaffection; Digi084 [Professor Charles Pattie]

[3]Hansard Society, Anti-Politics: Characterising and Accounting for Political Disaffection; Digi084 [Professor Charles Pattie]