10 Elections and voting

Voter turnout is a key indicator of the health of our democracy, with low turnout indicating that our democracy is not working as well as it should. The Political and Constitutional Reform Committee recently identified a number of reasons for the decline in voter turnout in recent decades, including political disengagement and a feeling that it is not worth voting.[1] This was reflected in our conversations with people. Some also said that candidates were not representative enough, and that there should be more diversity.[2] Open primaries for candidates were seen as one way of countering this.[3]

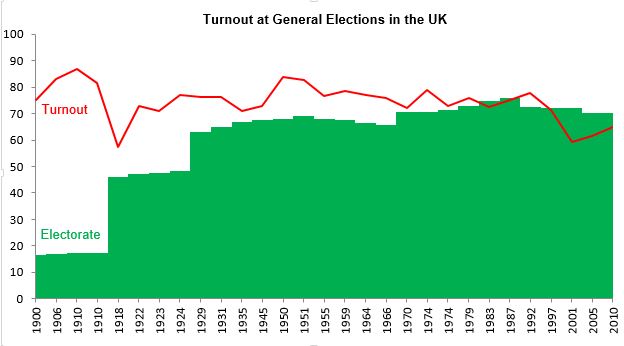

This graph shows voter turnout percentage in the UK along with the size of the electorate. The following list is the year of the general election followed by the percentage of electorate who voted: 1900, 75.1%; 1906, 83.2%; 1910, 86.8%; 1910, 81.6%; 1918, 57.2%; 1022, 73%; 1923, 71.1%; 1924, 77%; 1929, 76.3%; 1931, 76.4%; 1935 71.1%; 1945, 72.8%; 1950, 83.9%; 1951, 82.6%; 1955, 76.8%; 1959, 78.7%; 1964, 77.1%; 1966, 75.8; 1970, 72%; 1974, 78.8; 1974, 72.8; 1979, 76%; 1983, 72.7%; 1987, 75.3%; 1992, 77.7%; 1997, 71.4%; 2001, 59.4%; 2005, 61.4%; 2010, 65.1%.

This graph shows voter turnout percentage in the UK along with the size of the electorate. The following list is the year of the general election followed by the percentage of electorate who voted: 1900, 75.1%; 1906, 83.2%; 1910, 86.8%; 1910, 81.6%; 1918, 57.2%; 1022, 73%; 1923, 71.1%; 1924, 77%; 1929, 76.3%; 1931, 76.4%; 1935 71.1%; 1945, 72.8%; 1950, 83.9%; 1951, 82.6%; 1955, 76.8%; 1959, 78.7%; 1964, 77.1%; 1966, 75.8; 1970, 72%; 1974, 78.8; 1974, 72.8; 1979, 76%; 1983, 72.7%; 1987, 75.3%; 1992, 77.7%; 1997, 71.4%; 2001, 59.4%; 2005, 61.4%; 2010, 65.1%.

One reason why people do not vote is that they are not registered to vote and so are unable to do so on election day. We welcome the recent introduction of online registration for voting, which has now been used by nearly 2.4 million people, and has the potential to increase accessibility. We also support the important work by organisations such as the Electoral Commission (the independent body which supervises the electoral system in the UK) in educating people on how to register to vote. We fully support this year’s National Voter Registration Day on 5 February 2015. Information on how to vote and the new system of voter registration needs to reach those groups who are less likely to be registered, such as young people and homeless people.

Bite the Ballot is an organisation that campaigns to engage young people with politics and get them registered to vote. It has recently teamed up with TV presenter Rick Edwards and cross-party think tank Demos to create a Voter Advice Application for the 2015 election.

We note with concern the recent finding of the Political and Constitutional Reform Committee on under-registration of people from some Black and Minority Ethnic groups. It said:

“According to the Electoral Commission, some Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) groups are significantly less likely to be registered to vote compared to those identifying as White British… turnout for people from BME groups once they are registered to vote does not differ significantly from turnout for White British residents who are registered.”[4]

The Speaker’s Commission supports the committee’s call for further work to address this disparity.

10.1 Information about elections and voting

We were particularly concerned to hear that some people had not voted because they did not feel they knew enough about politics. Some said that they did not know how to decide who to vote for, and one person told us that they did not know how to vote.[5] One young person said simply: ‘‘I don’t vote because I don’t understand”.[6]

The Digital Democracy Commission strongly believes it is unacceptable that anyone should be unable to exercise their right to vote because they do not know how to vote. Not everyone has learned about elections and voting at school, although these are now included in the national curriculum. Where an individual’s family and friends are not active voters, their exposure to and knowledge of the process may be limited. The cycle of not voting within families was discussed at one discussion group for young citizens, in which some participants said that as members of their family did not vote, in the future they probably wouldn’t either.[7]

21. The Speaker’s Commission wishes to encourage increased efforts on voter education and recommends a fresh, bold, look at the national curriculum in this regard.

Voter turnout has decreased from 80%-65% between the 80s and 2010. Could digital means help engage voters? #MWDigital

— Kat Williams (@KatWilliams007) August 12, 2014Digital technology can help to make information about candidates and political parties more accessible. Several people said they would like an app to help them to decide how to vote, unaware that there are already websites and apps that do this.[8] Voter advice applications and websites can help citizens to decide who to vote for by asking about their views and comparing their answers to the policies of different parties. This is not something that Parliament could or should do on its website, because of the need to remain impartial. Not everyone will want an app, however, and many would find it useful just to be able to access information about candidates and parties in one place.

22. The Commission strongly encourages the political education bodies and charities to consider how to make available and publicise trustworthy information about candidates and their policies, including by means of voter advice applications.

23. The Digital Democracy Commission also notes a clear indication from a range of comments received that the profile and knowledge of the Electoral Commission needs to be improved, as it is a vital source of information to voters, with a website that is an Aladdin’s cave for those wishing to participate in the UK’s political process.

Voting Counts UK is a website created by 18 year old Rachael Farrington to help young people decide who to vote for.

It is obvious that anyone may want to know the result of an action, particularly if that action should be habit forming such as voting for the first time. Yet there is no single official online destination offering information about election results and there is a lack of consistency about how results are published online. Even local council websites offer data about council election results in a variety of formats. To counter this, details of votes cast at the general election could be transmitted electronically to one central database or ‘results bank’ as soon as they are declared. Thus the citizen would have one, indisputable source or destination online to see the result of their vote.

24. The Digital Democracy Commission recommends that the Electoral Commission consider how best to establish a digital ‘results bank’.

Similarly, information on the social characteristics of candidates and those elected is currently gathered in an ad hoc manner by different sources. The House of Commons Library could gather all of this data and produce a regular report on the background of MPs and candidates. This would create an officially recognised data source and improve the real-time data available for anyone to analyse. The Digital Democracy Commission believes that there is a demand for greater access to information about candidates and political parties, in different formats and via a range of channels, to help citizens exercise their democratic duties, and to know the results of elections.

25. The Commission fully endorses the draft Political and Constitutional Reform Committee recommendation that “the Government and the Electoral Commission should examine the changes which can be made to provide more and better information to voters, and should actively support the work of outside organisations working to similar goals.”[9]

10.2 Online voting

Currently, there are two main ways of voting in the UK—in person at a polling station on election day, or by post in advance. Online voting has been piloted on a small scale in the UK, but will not be available as an option in the 2015 general election. Many of the people we spoke to did not understand why they could not vote online, particularly young people. People are used to doing their banking and other day-to-day activities online and many feel that they should also be able to vote in this way.

Some people said that the inconvenience of having to vote in person was off-putting and suggested that online voting would help to increase voter turnout.[10] However, others said that there was little evidence of this.[11] One group of young people thought that online voting would be particularly useful for people in remote areas and others who do not have easy access to polling stations.[12] Others suggested it would help to overcome barriers to voting for Britons living abroad, military personnel posted overseas and those with disabilities. Some people felt that the ritual of making time to go to the polling station was important.

#digitaldemocracy @Meg_HillierMP @parliamentweek will online voting finally provide a secret ballot for blind people?

— RLSB Charity (@RLSBcharity) November 17, 2014Some people highlighted concerns about the security of online voting and the potential for cyber attacks and hacking.[13] Others raised concerns about voter intimidation and vote selling.[14] The Open Rights Group neatly summed up the concerns over the security of online voting:

“Voting is a uniquely difficult question for computer science: the system must verify your eligibility to vote; know whether you have already voted; and allow for audits and recounts. Yet it must always preserve your anonymity and privacy. Currently, there are no practical solutions to this highly complex problem and existing systems are unacceptably flawed.”[15]

We think that online voting has the potential greatly to increase the convenience and accessibility of voting, and we looked into the use of online voting in other countries. So far, 14 countries have used internet voting for binding political elections or referendums, but Estonia is the only one to have introduced permanent national internet voting.[16] It has an advanced system for verifying citizens’ identity online, but there have been concerns about the security of its system.[17] In New South Wales, Australia, the strategy of the electoral commission has been to recognise that there is not yet a “secure and reliable electronic voting system which removes all the known risks”.[18] It is building confidence in online voting by putting checks and balances in place and starting with a manageable segment of the electorate—people with disabilities and those who live a long way from a polling station.

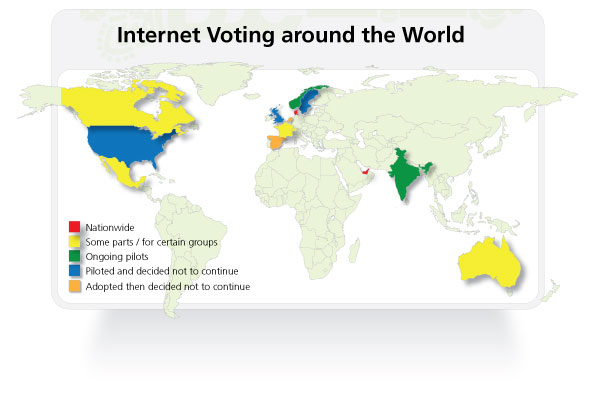

This image shows countries who have or have tried internet voting in the world. Countries who use internet voting nationwide are: The United Arab Emirates (from polling stations) and Estonia (from any device). Those who use internet voting for certain geographical parts or groups are: Australia (since 2007), Canada (since 2003), France (since 2003), Mexico (since 2012) and Switzerland (since 2003). Those countries who have ongoing pilots are India (since 2010 and Norway (since 2011). Countries who have piloted internet voting but decided not to continue are: Finland (2008), UK (2002), USA (2000). Countries which adopted internet voting and then decided to discontinue its use are: Netherlands (2004) and Spain (2003).

This image shows countries who have or have tried internet voting in the world. Countries who use internet voting nationwide are: The United Arab Emirates (from polling stations) and Estonia (from any device). Those who use internet voting for certain geographical parts or groups are: Australia (since 2007), Canada (since 2003), France (since 2003), Mexico (since 2012) and Switzerland (since 2003). Those countries who have ongoing pilots are India (since 2010 and Norway (since 2011). Countries who have piloted internet voting but decided not to continue are: Finland (2008), UK (2002), USA (2000). Countries which adopted internet voting and then decided to discontinue its use are: Netherlands (2004) and Spain (2003).

The Commission is confident that there is a substantial appetite for online voting in the UK, particularly among young people. It will become increasingly more difficult to persuade younger voters to vote using traditional methods.[19] It is only a matter of time before online voting is a reality, but first the concerns about security must be overcome. Once this is achieved, there will be an urgent need to provide citizens with access to online voting, and the UK must be prepared for this. The Electoral Commission has called on the Government to introduce a “comprehensive electoral modernisation strategy […] setting out how the wider use of technology in elections will ensure the achievement of transparency, public trust and cost effectiveness”.[20] The new online registration system could be a cornerstone of a future online voting system, although it would not solve the problem of verifying the identity of people when casting their vote online.

We support the draft recommendation of the Political and Constitutional Reform Committee on Voter Engagement in the UK, urging the introduction of online voting by 2020. We agree that this would make voting significantly more accessible. However, we also agree that concerns about electoral fraud and secrecy of the ballot would need to be addressed first.

26. In the 2020 general election, secure online voting should be an option for all voters.

[1]Political and Constitutional Reform Committee, Voter Engagement in the UK, 14 November 2014

[2]Leicester roundtable 4 September 2014; Discussion with Kenny Imafidon, 11 October 2014; Young people discuss e-democracy at Facebook, 9 May 2014

[3]Leicester roundtable 4 September 2014; Discussion with Kenny Imafidon, 11 October 2014

[4]Political and Constitutional Reform Committee, Voter Engagement in the UK, 14 November 2014

[5]Stockport roundtable 11 August 2014

[6]Leicester roundtable 4 September 2014

[7]Young people discuss e-democracy at Facebook, 9 May 2014

[8]Stockport roundtable 11 August 2014;Leicester roundtable 4 September 2014; Model Westminster contribution following workshop on 12 August 2014; Secondary students roundtable 18 July 2014

[9]Political and Constitutional Reform Committee, Voter Engagement in the UK, 14 November 2014

[10]Digi078 [WebRoots Democracy]; Digi031 [Dr Rachel Gibson, University of Manchester]; Model Westminster contribution following workshop on 12 August 2014;Michael Bolsover contribution on representation

[11]Spoken contribution on electronic voting by Katie Ghose, Q112; Digi047 [Councillor Jason Kitcat]; Digi075 [Open Rights Group];Digi072 [Foundation for Information Policy Research (FIPR)];UK Computing Research Committee

[12]Model Westminster contribution following workshop on 12 August 2014

[13]Spoken contribution on electronic voting by Katie Ghose, Q112; Spoken contribution on electronic voting by Andrew Colver, Q116; Digi047 [Councillor Jason Kitcat]; Digi072 [Foundation for Information Policy Research (FIPR)];Digi075 [Open Rights Group];Digi077 [Electoral Commission]; UK Computing Research Committee

[14]Spoken contribution on electronic voting by Professor bob Watt, Q99;Spoken contribution on electronic voting by Andrew Colver, Q116;Digi072 [Foundation for Information Policy Research (FIPR)]

[15]Digi075 [Open Rights Group]

[16] Collected from different sources: Jordi Barrat I Esteve, Ben Goldsmith and John Turner, International Experience with E-Voting, June 2012 and Smartmatic: A survey of Internet Voting

[17]Independent report on e-voting in Estonia

[18]NSW Electoral Commission, iVote strategy for the NSW State general election 2015

[19]Model Westminster contribution following workshop on 12 August 2014; Brighton roundtable 17 September 2014