7 Widening opportunities for genuine participation

Digital tools present significant opportunities for wider public engagement. However, these opportunities will succeed only if Parliament and MPs are prepared to listen to people’s views and take them on board. Here, we outline different ways that the public can engage with Parliament and discuss how some of these could be opened up.

7.1 Contacting MPs

Everyone has a link to Parliament through their MP, who is elected to represent their interests. People can contact their MP about local issues, or problems they are having with housing or local services, for example. They can do this by letter, email or in person at constituency surgeries or in Parliament.

People can also contact MPs and Members of the House of Lords (Peers) to lobby them about an issue they are interested in that they want Parliament to take action on. This kind of correspondence is increasing, partly because of online campaigns by organisations such as 38 Degrees, which encourage large numbers of people to lobby politicians on particular issues. This is good because it means that more people are engaging with their MP, but it also makes it more difficult for MPs to respond to their constituents on a personal level. One MP highlighted the difficulty of hearing quieter voices amid the noise of hundreds of emails:

“I receive around 600 emails each working day. Amongst them are the quiet individual messages that need particular help. They matter most and there is the growing risk that they will be missed. I believe it is becoming more difficult for an active MP to read their own Inbox. Even a dedicated member of staff is not a completely satisfactory substitute for the person who is elected. One point is this: modern communication includes the inadvertent and little noticed separation of MP from constituent.”[1]

We heard a range of views about how well MPs responded to constituents, including evidence from 38 Degrees that its members had a broadly positive experience, but some very negative ones.[2]

Social media adds another dimension, with a growing number of MPs using it to connect with constituents in an informal way about the issues they are interested in. A recent report from Demos outlined the importance of social media in connecting with young people:

“The use of social media is a way to get the message across to young people, but politicians need to learn to use it more effectively, and the message needs to be right.”[3]

Idea from the floor: an MP portal which can help MPs filter & understand all of their constituent's views #DDCVisits

— Digital Democracy (@digidemocracyuk) June 30, 2014As new communications channels emerge, the pressure on MPs to keep up will increase. Digital technology has the potential to help Parliament and MPs to manage their communications better.[4] Document Direct suggested that a more efficient case-load handling system would give MPs more time to engage with their constituents.”[5] We agree that if MPs were better supported in managing their digital communications, this would help them to respond more fully to their constituents. This in turn may help to ensure that constituents have a positive experience and are encouraged to engage with their MP or Parliament again.

14. The new parliamentary digital service should identify tools to help increase the volume and quality of interaction between MPs and their constituents. It should involve MPs and constituents in the development of these tools to ensure that an increase in communications is manageable by everyone involved.

We acknowledge that cyber-security is a growing and current concern to MPs, who naturally wish to ensure the confidentiality of their work and their constituents is protected. We also heard about another, less positive, side of digital communications—cyber harassment and trolling. The Speaker has had cases raised with him directly by MPs. The case of ‘women on banknotes’ campaigner Caroline Criado-Perez, championed by Stella Creasy MP, and the horrific abuse of the social media tool Twitter has been well reported. While freedom to campaign for causes and express opinions is vital in a fully functioning democracy, public figures, including MPs, are increasingly likely to be subject to cyber harassment.

15. The Commission acknowledges the work in this area that has been conducted by others, but recommends that:

- the political parties urgently review what measures they have in place to support candidates at the next General Election who may be subjected to abuse of digital technology in the form of cyber harassment;

- the House urgently reviews measures to support MPs subject to cyber harassment;

- this review is carried out in tandem with the ongoing work regarding improving cyber-security to ensure that MPs can carry out their duties effectively, efficiently and in the sure knowledge that the confidentiality of their constituents is protected.

7.2 E-petitions

Another way that people can flag up to MPs and Parliament an issue that they are concerned about is by starting or signing a petition. People have been signing paper petitions for hundreds of years, but they can now do it online as well, on the Government e-petitions website.[6] Because e-petitions are accessible and easy to use, they can be a good way of raising issues of concern with the Government and Parliament.[7] They tend to focus on very specific issues and can be shared easily, and this makes it easy to launch nationwide campaigns, particularly through platforms set up by organisations such as Change.org.[8]

However, some people doubted how much impact e-petitions had. Dr Andy Williamson said:

“[The e-petitions system] demonstrates some very limited successes but overall the ability of the public to achieve any real change through the process is low. The process as implemented does not lend itself well to a modern citizen-centric democracy; too many gatekeepers within Parliament are able to (and regularly do) disrupt it.”[9]

We support the recent recommendation by the House of Commons Procedure Committee for a new e-petitions system hosted on Parliament’s website, overseen by a committee of MPs.[10] Such a committee would have a much wider range of possible responses to both paper and e-petitions than exists under the current system, including:

- writing to the person who launched a petition

- asking them to come and speak to the committee

- referring a petition to another suitable committee to be discussed (for example, the Health Committee or the Home Affairs Committee)

- seeking further information from the Government about the issue raised by a petition

- putting forward petitions for debate.

We think these changes would go some way towards making petitions a more effective way for the public to have genuine engagement with Parliament and a greater chance of making an impact. However, it is important that there is better feedback available on what impact e-petitions have had—for example, whether they got a high number of signatures or triggered a debate in the House of Commons or a change in the law. This will help the public to see that they can have an impact, and will enable them to compare how effective different e-petitions have been.

7.3 Contributing to the work of select committees

Select committees look at what the Government is doing and how well it is performing. Most of them look at the work of particular Government departments—for example, Education and Health—but some are more cross-cutting, such as the Environmental Audit Committee. These committees work mainly by conducting inquiries into specific issues they are concerned about. When they do this they invite the public to give their views, and this is called giving evidence to the committee. Much of the evidence that select committees receive is from organisations, businesses and experts, although some members of the public also send in their views. A few of the people we spoke to had sent their views to a committee, but many of them did not know how to do this, and some had never heard of select committees.

We see great potential for using digital to strengthen links between Parliament and the public simply by raising awareness of select committee work and encouraging greater public involvement. We note that committees have already been using social media to encourage public engagement with their work. Many have Twitter accounts and some live tweet during oral evidence sessions, when people are invited to talk directly to the committee. Committee web pages also have icons that people can click on to share the page on social media platforms, including Facebook and Linkedin.

Some committees have also used hashtags to source questions to witnesses. For example, the highly successful #AskGove and #AskPickles hashtags were used to invite questions to Government Ministers.[11]

The Communities and Local Government Committee asked people to suggest questions on Twitter for it to ask the Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government in an evidence session. Lots of people suggested questions, and some of those questions were asked. One of the questions led to a change in the law. The committee followed up by publishing a summary of the process and outcomes.

The process was so successful that it was recently repeated, and the hashtag has also been a useful way of following up outcomes from the first session.

We commend this approach and would like to see further experimentation of this kind. However, we also note that while Twitter is a useful tool, it is not as widely used as other social media and therefore is not always the best medium for reaching out to new audiences. The Hansard Society flagged up the risks of placing too much emphasis on Twitter:

“[Twitter] has a far smaller reach than Facebook, less news is shared on it (although more news is broken) and in many ways, given the number of politicians, journalists, campaigners and lobbyists on the site, it replicates the traditional Westminster bubble.”[12]

As we have already outlined, many people who say they are turned off by politics are interested in specific issues. There is potential for matching people’s interests to select committee work and encouraging engagement in that way. One way of doing this is by forging links with online communities that share interest in an issue the committee is looking at. Some committees have been doing this successfully in conjunction with the parliamentary digital outreach team. See the case study below for one example of this.

Background: As part of its inquiry into Future Army 2020, the Defence Committee hosted a series of discussion threads on the Army Rumour Service forum—an unofficial forum for soldiers, veterans and interested others. This gave it the opportunity to hear the experiences of reservist and full‐time troops who would not usually have their voices heard as part of a Committee inquiry. Across 23 threads on the forum, which discussed aspects of the committee’s inquiry, there were 45,614 views.

Result: The forum was referenced a number of times in the oral evidence sessions and in the committee’s report, which said:

“During the course of our inquiry, the Army Rumour Service hosted a web forum to enable us to hear the views of interested parties on the Army 2020 plan which we used to inform our questioning of witnesses. The forum received 494 comments from 171 contributors. We are grateful to the Army Rumour Service for hosting this forum for us and to all those who contributed.”[14]

Feedback from forum users was predominantly positive, with one commenting:

Sarastro: I would suggest that the value of contributions here (and there is some) is that it offers MPs another source which helps them develop the deeper knowledge mentioned above, so that they might ask the difficult questions successfully.

This approach of building relationships is a good way of reaching out to people and involving them in select committee work. However, it is also resource-intensive and this places a limit on how much it can be used. We think this work should continue, but we would like to see other, less resource-intensive uses of digital to ‘go where people are’.[15] For example, select committees could experiment with targeted advertising in online spaces. They could also use tools to develop digital listening skills and tune into online conversations to get a better idea of public opinion.

16. Select Committees should make greater use of social media and online advertising to reach out to new audiences and raise awareness of their work. They should also experiment with using digital to involve people more in committee work.

7.4 Opening up the law-making process

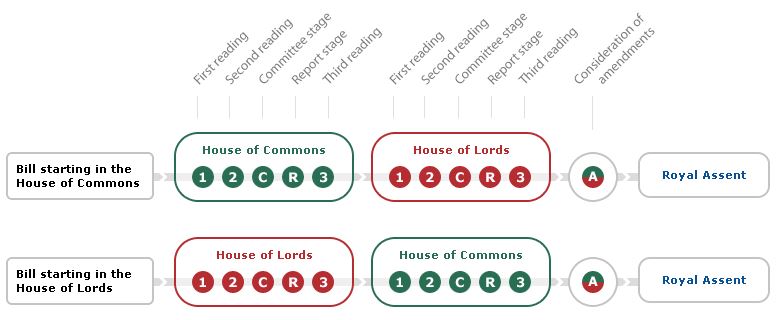

One of Parliament’s key functions is making laws. It does this by looking in detail at draft laws, or bills, that the Government wants to make into law. This process is broken down into several stages, which are outlined below in figure 7. When a bill has passed through all these stages—in both the House of Commons and the House of Lords—it becomes a law and is known as an Act of Parliament.

This image shows the passage of a Bill through Parliament. A Bill is a proposal for a new law, or a proposal to change an existing law, presented for debate before Parliament. A Bill can start in the Commons or the Lords and must be approved in the same form by both Houses before becoming an Act (law). The stages are as follows: first reading (title is read out in the House of Commons or the House of Lords), second reading (a debate in the House of Commons or House of Lords

This image shows the passage of a Bill through Parliament. A Bill is a proposal for a new law, or a proposal to change an existing law, presented for debate before Parliament. A Bill can start in the Commons or the Lords and must be approved in the same form by both Houses before becoming an Act (law). The stages are as follows: first reading (title is read out in the House of Commons or the House of Lords), second reading (a debate in the House of Commons or House of Lords

Currently, opportunities for the public to contribute to the law-making process within Parliament are limited. The main way is by contacting an MP or Peer and raising any concerns with them, and so is quite indirect. Many of the people we heard from thought that Parliament should open up the law-making process to the public, and they suggested different stages where people could get involved:[16]

- at the very beginning, so that the public could suggest topics for bills

- policy development stage: when the government consults on its proposals through a document known as a ‘green paper’

- pre-legislative scrutiny: when a policy is translated into a bill but before it is issued officially in Parliament

- Queen’s Speech: immediately after the Government has announced in the Queen’s Speech which bills it intends to issue that year

- Second Reading: at the time the Commons or the Lords debates the overall principles in the bill and votes on whether it should go on for further discussion, known as the Second Reading of the bill

- Committee Stage: when MPs or Lords debate the bill in detail in a committee

- Post-legislative scrutiny: after the bill has become law, the public could help to review how effective the new law had been.

We agree that Parliament should do more to open up the law-making process, which is one of its key functions, to the wider public. The easiest time for people to get involved is in the earlier stages, when the Government is still forming its policies and thinking about what it wants to put in draft laws. There is already some potential to do this, when the Government consults on policies, but these opportunities are not consistent. Some people have also suggested that they are not open enough and should enable more discussion between the public and policymakers.

By the time policy ideas have been written into draft laws, it becomes much more difficult for people to comment on and understand them because they are complex documents with lots of jargon and legal terms.[17] We have recommended that this language should be made more accessible. However, even with these improvements, the later stages of the law-making process will be more suited to more technical and specialised input.

Parliament has already experimented with public consultation between the second reading and committee stages. These experiments, known as public reading of bills, were successful in attracting interest, but less successful in having an impact on the bills being considered.[18] This was partly because it is difficult to amend a draft law once it has reached Parliament. By that stage, the Government has a firm idea of what it wants the law to achieve and is less likely to be persuaded that changes are necessary.

We believe that the best time to involve the public is in the policy development and pre-legislative stages, when the public could suggest technical and policy changes. However, we would like to see a period of experimentation at various stages of the law-making process with the aim of finding a way to achieve genuine public input.

17. The House of Commons should experiment with new ways to enable the public to contribute to different stages of the law-making process, primarily by digital means.

7.5 Contributing to parliamentary debates

As well as debating draft laws, MPs debate issues, some of which are national and others local or constituency-related. Currently, there is rarely any opportunity for the public to get involved in House of Commons debates, but digital technology could help to involve citizens. The House has already carried out promising experiments to set up online discussions, some in collaboration with partner organisations, linked to parliamentary debates and committee inquiries.[19]

The House of Commons started to use a second chamber, known as Westminster Hall, in 1999 because of the limited time available for debates in the main chamber. Now, debates go on in both chambers at the same time, enabling MPs to discuss more topics. In the past year, topics debated in Westminster Hall have included zero-hours contracts, the A303, football club bankruptcy, badger culls, domestic violence, the humanitarian situation in Gaza and voting at 16. These debates tend to be more informal than those in the Chamber.

We believe that the debates in Westminster Hall provide an excellent and unique opportunity to experiment with opening up House of Commons debates to the public and create a direct link between what is being said in Parliament and the people it represents. People interested in the topic for debate should have the opportunity to discuss it online, before the House of Commons debate. MPs could contribute or simply observe. We believe this would help to inform their contributions and enhance the debate in Parliament. Currently, few people are aware of the existence of Westminster Hall debates, although they are part of the large amount of work which happens outside of the main House of Commons chamber, which is more often seen on TV. This new initiative would therefore not only open up House of Commons debates to the public, but also highlight more of the hidden work of Parliament. If successful, the forum could be used for debates in the main chamber.

18. We believe the public want the opportunity to have their say in House of Commons debates; we also believe that this will provide a useful resource for MPs and help to enhance those debates. We therefore recommend a unique experiment: the use of regular digital public discussion forums to inform debates held in Westminster Hall. This innovation might be known as the “Cyber Chamber” or “Open House.” If at the end of the next Parliament it has been successful, it could then be extended to debates in the main House of Commons chamber itself.

7.6 Questions to Ministers and the Prime Minister

Ministers regularly attend question time in the House of Commons to answer questions from MPs about Government policies and implementation. Once a week, in Prime Minister’s Questions (PMQs), MPs have the opportunity to hold the Prime Minister to account. This is probably the most well-known parliamentary activity, as it is regularly shown on television. Many of the people we spoke to had seen it at one time or another, and some told us that they watched or listened to it regularly. People had differing views on how Prime Minister’s Questions reflects on Parliament, with some finding it engaging and others finding the robust exchanges off-putting. This chimes with what the Hansard Society recently found when it looked at people’s attitudes to PMQs:

“The survey results similarly reflected…disenchantment with PMQs amongst the wider public, with 67% of respondents agreeing that ‘there is too much party political point-scoring instead of answering the question’, 47% agreeing that PMQs ‘is too noisy and aggressive’ and just 12% agreeing that PMQs ‘makes me proud of our Parliament’.”[20]

Some of the people we heard from thought that the public could be more involved with Prime Minister’s Questions, for example by proposing questions for the Prime Minister. Professor Christian Fuchs suggested that there should be a YouTube channel, which he called 'QTube', on which people could propose questions.[21] People could then vote on the questions proposed, with the most popular questions being put to the Prime Minister, perhaps in a separate Prime Minister’s Questions for the public. Other people suggested similar systems using Twitter or other platforms.[22] Realistically, this would be a supplement to, and not an alternative to, the traditional PMQs format.

This method of using digital media to source questions or ideas from the public, known as crowd-sourcing, has proved successful for select committees. The Commission believes that extending this approach would help to increase the accountability of Ministers to the public. We would like to see Parliament experiment further in this area, by crowd-sourcing questions for Ministers, or the Prime Minister, on a more regular basis and in the chambers of the House, rather than just in committees.

19. The House of Commons should experiment with new ways of enabling the public to put forward questions for ministers.

[1] Peter Bottomley, online response on representation

[2]David Babbs, spoken contribution on engagement, 15 June 2014, Q44

[3]Demos, Tune In, Turn Out, 29 December 2014

[4]Digi004 [David Durant]; Digi038 [Document Direct]

[7]Martin Fowkes online response 1001258902

[9]Digi018 [Dr Andy Williamson]

[10]Procedure Committee, E-petitions: a collaborative system, 4 December 2014

[11]Education Committee, Michael Gove answers #AskGove twitter questions; Secretary of State asks the public’s #AskPickles questions

[12]Digi089a [Hansard Society]

[13]Digi028 [Lucy Denton, Digital Outreach Team]

[14]Defence Committee, Future Army 2020, 6 March 2014

[15] See chapter 5 on Relating Parliament’s work to people’s lives for more on going to where people are.

[16]Student forum discussion on legislation; Digi003 [Involve]; Model Westminster roundtable, 12 August 2014; Digi004 [David Durant]; Digi005 [Paul Robinson]; Digi016 [Mark D. Ryan and Gurchetan S. Grewal, University of Birmingham]; Digi019 [Argyro Karanasiou, (Centre for Intellectual Property Policy & Management, Bournemouth University)]

[17]Oral evidence to the Commission on legislation, 18 March 2014.

[18]House of Commons Library standard note, public reading stage of bills, 19 March 2014

[19]Digi028 [Lucy Denton, Digital Outreach Team]

[20]Hansard Society, tuned in or turned off: public attitudes to PMQs