6 Reaching out to under-represented groups

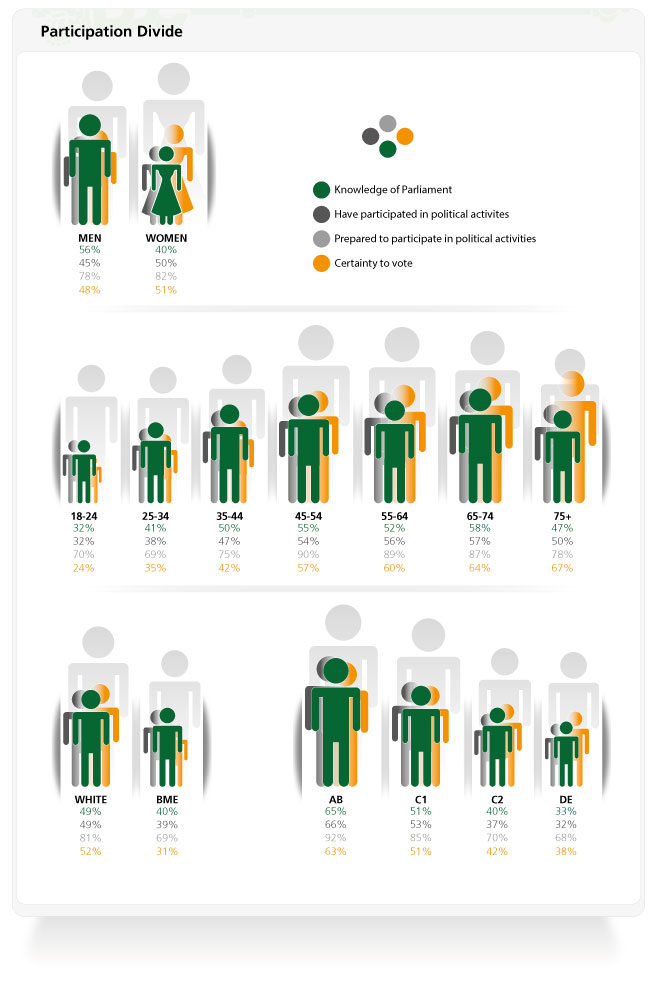

As we have outlined, some people are more likely than others to take part in democratic activities such as voting, signing an e-petition, or trying to influence political decision-making.[1] Those less likely to participate include women, people from lower socio-economic groups, young people and the less educated.[2]

This image shows the differences between different demographic groups. Breakdown 1: perceived knowledge of Parliament, percentage refers to those who know at least a fair amount. Gender: Men 56%, Women 40%; Age: 18 to 24 year olds 32%, 25 to 34 year olds 41%, 35 to 44 year olds 50%, 45 to 54 year olds 55%, 55 to 64 year olds 52%, 65 to 74 year olds 58% and 75 plus year olds 47%; Social Class: class AB 65%, class C1 51%, class C2 40%, class DE 33%; Ethnicity: White 49%, BME 40%. For those who are absolutely certain to vote: Gender: Men 48%, Women 51%; Age: 18 to 24 year olds 24%, 25 to 34 year olds 35% 35 to 44 year olds 42%, 45 to 54 year olds57%, 55 to 64 year olds 60%, 65 to 74 year olds 64%, and 75 year olds plus 67%; Social class: class AB 63%, class C1 51%, class C2 42%, and class DE 38%; Ethnicity: White 52%, BME 31%. Breakdown 2: Political activities actual and potential. The actual percentage is those who have completed a political activity to influence decisions, laws or policies in the last 12 months. The potential percentage is whether they would be prepared to undertake any political activities if they felt strongly about an issue. Gender: men actual 45% potential 78%, women actual 50% potential 82%; Age: 18 to 24 year olds actual 32% potential 70%, 25 to 34 year olds actual 38% potential 69%, 35 to 44 year olds actual 47% potential 75%, 45 to 54 year olds actual 54 % potential 90%, 55 to 64 year olds actual 56% potential 89%, 65 to 74 year olds actual 57% potential 87%, 75 year olds plus actual 50% potential 78%; Social class: AB class actual 66% potential 92%, C1 class actual 53% potential 85%, C2 class actual 37% potential 70%, DE class actual 32% potential 68%; Ethnicity: White actual 49% potential 81%, BME 39% potential 69%. The final category is certainty to vote in a general election. Gender: men 48%, women 51%, age: 18 to 24 year olds 24%, 25 to 34 year olds 35%, 35 to 44 year olds 42%, 45 to 54 year olds 57%, 55 to 64 year olds 60%, 65 to 74 year olds 64%, and 75 years old plus 67%; Social class: AB class 63%, C1 class 51%, C2 class 42%, DE class 38%. Ethnicity: white 52%, BME 31%.

This image shows the differences between different demographic groups. Breakdown 1: perceived knowledge of Parliament, percentage refers to those who know at least a fair amount. Gender: Men 56%, Women 40%; Age: 18 to 24 year olds 32%, 25 to 34 year olds 41%, 35 to 44 year olds 50%, 45 to 54 year olds 55%, 55 to 64 year olds 52%, 65 to 74 year olds 58% and 75 plus year olds 47%; Social Class: class AB 65%, class C1 51%, class C2 40%, class DE 33%; Ethnicity: White 49%, BME 40%. For those who are absolutely certain to vote: Gender: Men 48%, Women 51%; Age: 18 to 24 year olds 24%, 25 to 34 year olds 35% 35 to 44 year olds 42%, 45 to 54 year olds57%, 55 to 64 year olds 60%, 65 to 74 year olds 64%, and 75 year olds plus 67%; Social class: class AB 63%, class C1 51%, class C2 42%, and class DE 38%; Ethnicity: White 52%, BME 31%. Breakdown 2: Political activities actual and potential. The actual percentage is those who have completed a political activity to influence decisions, laws or policies in the last 12 months. The potential percentage is whether they would be prepared to undertake any political activities if they felt strongly about an issue. Gender: men actual 45% potential 78%, women actual 50% potential 82%; Age: 18 to 24 year olds actual 32% potential 70%, 25 to 34 year olds actual 38% potential 69%, 35 to 44 year olds actual 47% potential 75%, 45 to 54 year olds actual 54 % potential 90%, 55 to 64 year olds actual 56% potential 89%, 65 to 74 year olds actual 57% potential 87%, 75 year olds plus actual 50% potential 78%; Social class: AB class actual 66% potential 92%, C1 class actual 53% potential 85%, C2 class actual 37% potential 70%, DE class actual 32% potential 68%; Ethnicity: White actual 49% potential 81%, BME 39% potential 69%. The final category is certainty to vote in a general election. Gender: men 48%, women 51%, age: 18 to 24 year olds 24%, 25 to 34 year olds 35%, 35 to 44 year olds 42%, 45 to 54 year olds 57%, 55 to 64 year olds 60%, 65 to 74 year olds 64%, and 75 years old plus 67%; Social class: AB class 63%, C1 class 51%, C2 class 42%, DE class 38%. Ethnicity: white 52%, BME 31%.

The Commission sees the potential of digital technology to increase public participation with Parliament and the democratic process. However, it is important to ensure that it does not simply make it easier for those who are already engaged to have more of a say.[3] Professor Charles Pattie outlined the risk:

“Those already politically engaged are quick to adopt web technologies as yet further ways of engaging. By and large, those who are politically marginalised just do not. Far from being a potential ‘weapon of the weak’ or even just a leveller of the participatory playing field, it seems, web technologies in practice are far more likely to entrench existing inequalities in political access.”[4]

If Parliament is to avoid simply giving a louder voice to the politically engaged and tech-savvy, it must complement its digital engagement opportunities with strategies to reach out to groups who are less likely to engage.[5] This will involve looking at the barriers to involvement and helping people to overcome them. We have already set out how it might go some way towards doing this by helping to improve people’s understanding of Parliament and its activities. Some people also suggested that Parliament should present information in a more dynamic way, rather than sounding “as dull as ditchwater” if it wanted to engage with new audiences.[6]

Comment from the floor: engagement can't just be from the 'usual suspects' it needs 2 b with ordinary people with ordinary lives #DDCEngage

— Digital Democracy (@digidemocracyuk) July 2, 2014The Commission understands that most people will not want to participate in parliamentary activities on a frequent basis, but we are convinced that people will be interested in getting involved when Parliament is considering issues that they care about if they think their involvement can make a difference. As one of the people we spoke to put it:

“A citizen’s relationship with Parliament might not be one they have all the time, but one they dip in and out of depending on what issues are being discussed and are affecting them.”[7]

The DDC also notes the importance of face-to-face interaction. Digital has the potential to widen participation on a large scale, but people are more likely to get involved when they are asked to do so in person.[8] One group suggested that democracy cafés—public spaces where people could go to talk about politics in a safe space and get help with going online—might be one way of encouraging people to get involved.

12. As part of its new, professional communications strategy the House of Commons should, in 2015-16, pilot and test new online activities, working with national and local partners, to target and engage specific groups who are not currently engaged in democratic processes. These target groups could include, for example: 18-25 year olds not at university, people with learning difficulties, homeless people and people living in communities with very low voter turnout.

6.1 Young people

The Commission is particularly interested in the role of young people in our democracy. We are aware that 18 to 24-year-olds are less likely to vote than other age groups.[9] We also share the concerns of the Political and Constitutional Reform Committee that “there will be severe and long-lasting effects for turnout at UK elections, with consequent implications for the health of democracy in the UK” if a generation of young people continue not to vote as they get older.[10] Some of the young people we spoke to also share this concern. One group felt there was a vicious circle:

“Young people are not listened to because they are not voting in sufficient numbers, therefore their concerns are not perceived as important election winning manifesto items; politicians represent those from whom they are likely to garner votes.”[11]

There is a perception that young people are apathetic about politics, but that has not been our experience from our interactions with young people. Many of the young people we spoke to were interested in political issues, and some were also involved with local community groups and initiatives. The evidence we have seen suggests that young people are interested in issues that affect their lives, but they feel that party politics and Parliament are not relevant to them.[12] Kenny Imafidon, who has written about youth engagement with politics and Parliament, told us:

“Young people are not apathetic to politics they are just apathetic to party politics. Whenever young people are given the genuine opportunity to engage or influence decision-makers they always take it."[13]

Brian Loader of York University told us that young people are “absolutely disillusioned and fed up with traditional mainstream politics”, and we saw some evidence of this.[14] One group we spoke to at a British Youth Council convention in Birmingham said that they were interested in engaging in political activities but felt that MPs and Parliament were inaccessible and were not interested in hearing from them.[15] Another group said they associated politicians with ‘Punch and Judy’ politics, and that the white, middle-class politicians they saw on television were not representative of the society they lived in.[16]

Perhaps the biggest barrier to engaging with Parliament and politics that young people experience is a lack of knowledge about political and parliamentary processes. That is why we are recommending that political education should be improved.[17] The way that information about Parliament is presented is also important. Kenny Imafidon told us that “the political system is presented in such a complex and boring way that it becomes a waste of time and energy to try and get to grips with”, and that, “engaging with Parliament and politicians feels impossible to most young people."[18] We have already outlined how the use of video and bite-sized content could help to make information about Parliament and political issues more accessible.[19] It was also suggested that ambassadors such as youth organisations, respected celebrities, vloggers and young leaders could help to connect young people with Parliament and political activity.[20]

Social media and other digital channels were seen as a good way of connecting with young people because many of them spend a lot of time on these platforms.[21] Brian Loader outlined four key issues for politicians to consider when using social media to connect with young people:

- “Top-down one-way communication channels between Parliament and citizens need to be re-assessed…Young people use social media to connect to each other and not to governments…or other traditional institutions. Communication channels therefore need to be co-constructed together with citizens if they are to be effective.

- Young citizens can no longer be regarded as dutiful citizens…They are far less likely to be deferential and far more likely to be critical citizens whose respect and trust needs to be earned.

- Neither should young people be regarded as a homogenous group. Their experiences as citizens are shaped by a range of factors including social class, gender, race, sexuality, geography and the like.

- Increased use of social media for surveillance means that young citizens are increasingly sceptical about new media and the state.”[22]

Whichever channels are used, it is important that when Parliament and MPs engage with young people, they reinforce a positive message that Parliament is relevant to their lives and that their opinions are valued. One way of doing this would be by helping young people to see that they can have an impact on what Parliament does and on political decision-making.

E-petitions can be a quick and easy way of participating in a democratic process that may have a political impact.[23] We think that Parliament should collaborate with schools, colleges and youth organisations to increase awareness of this avenue of campaigning and connecting with Parliament and politics. Later in this chapter, we look at e-petitions in more detail and discuss forthcoming changes to the system that might increase their impact.

We also see potential to strengthen links between Parliament’s day-to-day activities and some of its engagement work through competitions such as Lights, Camera, Parliament!

The Lights, Camera, Parliament! competition runs every year.[24] Last year’s challenge to young people was to submit a short film about a new law they would like to see introduced. The winners, from Coombe St Nicholas School, made a film about labelling products with information about whether child labour had been used in their production.[25] Since then, Baroness Garden and Baroness Andrews have formally requested a question for short debate in the House of Lords on the subject.

More debates of this kind, linking issues that young people are interested in to Parliament’s work, would help young people to see how Parliament is relevant to them.

13. The House of Commons should take further steps to improve active involvement by young people. This might include:

- encouraging young people to participate in the e-petitions system;

- youth issue focussed debates which involve young people and MPs.

[1]Hansard Society, Anti-Politics: Characterising and Accounting for Political Disaffection;

[2]Hansard Society, Anti-Politics: Characterising and Accounting for Political Disaffection; Digi084 [Professor Charles Pattie]

[3]Digi018 [Dr Andy Williamson]; Digi084 [Professor Charles Pattie]; Digi089a [Hansard Society]

[4]Digi084 [Professor Charles Pattie]

[5]Digi018 [Dr Andy Williamson]

[6]Digi89b Britain Thinks and the Hansard Society summary of workshop ‘A listening Parliament?’

[7]Edinburgh Roundtable 16 June 2014

[8]Digi084 [Professor Charles Pattie]

[9]House of Commons Library Standard note Elections: Voter turnout January 2014

[10]Voter Engagement in the UK: Political and Constitutional Reform Committee

[11]Model Westminster contribution following workshop on 12 August 2014

[12]Discussion with Kenny Imafidon, 11 October 2014; Dr Andy Williamson, spoken contribution on representation, Q24;Brian Loader, spoken contribution on engagement, Q74;British Youth Council Convention, Birmingham roundtable, 11 October 2014; Brighton roundtable 17 September 2014, British Youth Council Convention, Birmingham roundtable 11 October 2014; Secondary students roundtable 18 July 2014;

[13]Discussion with Kenny Imafidon, 11.10.14

[14]Spoken contribution on engagement, Q74;

[15]British Youth Council Convention, Birmingham roundtable 11 October 2014

[16]Young people discuss e-democracy at Facebook, 9 May 2014

[17] See section 2 for more on political education.

[18]Discussion with Kenny Imafidon, 11 October 2014

[19]Young people discuss e-democracy at Facebook, 9 May 2014

[20]Hardcopy or hashtag workshops October and November 2014; Discussion at the British Youth Council Convention in Birmingham, 11 October 2014; Young people discuss e-democracy at Facebook, 9 May 2014; Kenny Imafidon discussion 11 October 2014;

[21]Digi095 [Brian Loader, University of York]; Young people discuss e-democracy at Facebook, 9 May 2014; Brighton roundtable 17 September 2014; Discussion with Kenny Imafidon, 11 October 2014; Hansard Society, Audit of Political Engagement 11

[22]Digi095 [Brian Loader, University of York]

[23]British Youth Council Convention, Birmingham, 11 October 2014; Martin Fowkes online response 1001258902

[24]Parliament’s Education Service competition: Lights, camera, Parliament!

[25]A new child labour law: video by Coombe St Nicholas School