9 Tackling digital exclusion

Some people go online and use digital every day on their phone, tablet or other device, whereas others rarely, if ever, go online. The division between these groups is sometimes referred to as the digital divide. In practice, there will be people with a range of digital skills in between, but there is still a clear division between those who have the means and confidence to use digital and those who do not.

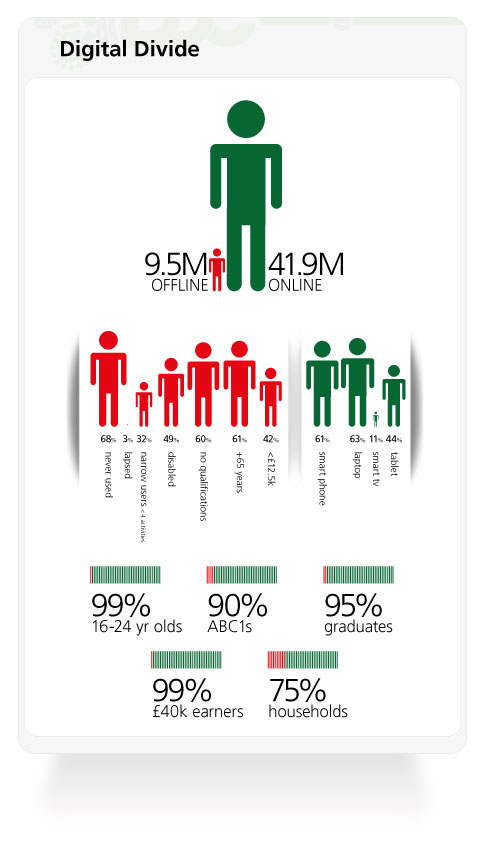

This image shows who is offline and who is online in the UK. It depicts that those offline tend to be people from low income households, the elderly and uneducated. Those online tend to be better off, young and educated. The number of those not online in the UK is 9.5 million people. Out of those not online, 49% are disabled; 61% are over 65 years of age; 42% are from low income households; and 60% hold no formal qualifications. The majority (9 million) of those offline do not have the basic skills required to use the internet. 68% of those not online have never used the internet, 32% are only very narrow users. In contrast, 41.9million of people in the UK are online. 99% of 16 to 24 year olds are online, 90% of those from social classes AB and C1, 95% of graduates, and 99% of those who earn over £40K.

This image shows who is offline and who is online in the UK. It depicts that those offline tend to be people from low income households, the elderly and uneducated. Those online tend to be better off, young and educated. The number of those not online in the UK is 9.5 million people. Out of those not online, 49% are disabled; 61% are over 65 years of age; 42% are from low income households; and 60% hold no formal qualifications. The majority (9 million) of those offline do not have the basic skills required to use the internet. 68% of those not online have never used the internet, 32% are only very narrow users. In contrast, 41.9million of people in the UK are online. 99% of 16 to 24 year olds are online, 90% of those from social classes AB and C1, 95% of graduates, and 99% of those who earn over £40K.

In the past decade there has been a rapid move to delivering commercial and Government services online. For some people, this has made it easier to access information and services, but those who are not online will have benefited less. Digital inclusion is about making sure that people are not excluded from the services they want and need, and to ensure everyone has equal opportunities to access the benefits that the digital world brings. Around a fifth of UK adults lack basic digital skills and 16% are not online.[1]

It is promising to see that the proportion of people who are using the internet has been increasing steadily in recent years.[2] But certain groups are more likely to be “digitally disengaged”, including older people, those with disabilities, and people without qualifications.[3]

Key barriers to getting online include lack of interest, confidence and/or know-how; financial constraints; poor broadband access; a preference for doing things in person; and fears about security.[4] The Government has taken steps to address those barriers and reduce digital exclusion in its digital inclusion strategy.[5]

If Parliament is to become more accessible and open, it too, will need to have a strategy for ensuring that the digitally disengaged are not excluded from understanding or engaging with its work. As the Democratic Society put it:

“Parliament must play its part in addressing the digital divide and digital literacy. Not everyone has access to the Internet and many do not know how to use online resources even if they are regular internet users.”[6]

We heard a number of different ideas for how Parliament could do this. One suggestion was that Parliament could form partnerships with community groups to help those less able to use digital to feed their views into Parliament. For example, a group in Chesterfield suggested that Parliament could train local community group leaders to help people to upload submissions to a select committee or to engage in other ways online. For those people who would have difficulty using digital at all, these local group leaders could act as an intermediary—listening to their views and inputting them digitally on their behalf.[7] Some organisations already provide this kind of service, as can be seen in the example below.

The Business Innovation and Skills Committee recently asked for people’s views on adult literacy and numeracy, and encouraged them to give their views by video.[8] Several organisations helped people to do this. For example, staff at St Mungo Broadway, a homeless charity and UK online centre, helped people to create a YouTube submission; the writer in residence at HMP Leicester compiled the prisoners’ submissions; and teachers from Leicester College helped learners to submit an audio-visual submission. At Robin Hood Junior School, a 6-year-old pupil used his skills to help record his teacher’s submission.

Parliament’s outreach team works with groups in the community, but it could do more to target the most affected groups by identifying relevant community support organisations and helping them to provide this kind of service, by giving training, information and other support. The Commission believes that a ‘digital first’ approach (using digital as the primary channel for information and using printed documents only where there is a clear need to do so) should be pursued. However, until UK-wide community support services are widely available, Parliament should continue to help the digitally excluded in other ways. For example, it should continue to make available on request free paper copies of parliamentary reports and other documents, where appropriate.

Digital exclusion is not a reason for Parliament to hold back the drive to become more digital. Digital has the potential to improve dramatically the relationship between Parliament and citizens, and everyone should benefit from this. As the examples above show, people who are not online can engage digitally when they are given the right support to contribute to Parliament’s work on an issue they care about. This can be a mix of direct support—helping people to get online or learn digital skills—and indirect support, through a trusted local intermediary, friend or family member.

20. Parliament should step up its work to build links with community organisations and services to help ensure that the digitally excluded are given local support to engage with Parliament online.

[1]Media Literacy: Understanding Digital Capabilities follow-up, 2013, BBC, Ipsos Media CT; Media Literacy: Understanding digital capabilities Final Report, 2014, BBC, Ipsos Media CT

[2]Media Literacy: Understanding digital capabilities Final Report, 2014, BBC, Ipsos Media CT

[3]Media Literacy: Understanding Digital Capabilities follow-up, 2013, BBC, Ipsos Media CT; Media Literacy: Understanding digital capabilities Final Report, 2014, BBC, Ipsos Media CT; Tinder Foundation Disability and Digital Inclusion Blog 3 December 2014;

[4]Digi061 [Carnegie UK Trust]; Digi065 [Arqiva]; Media Literacy: Understanding digital capabilities Final Report, 2014, BBC, Ipsos Media CT

[5]Government Digital Inclusion Strategy, December 2014

[6]Digi015a Democratic Society

[7]Roundtable Chesterfield 30 June 2014

[8]Business Innovation and Skills Committee inquiry and report into adult literacy September 2014